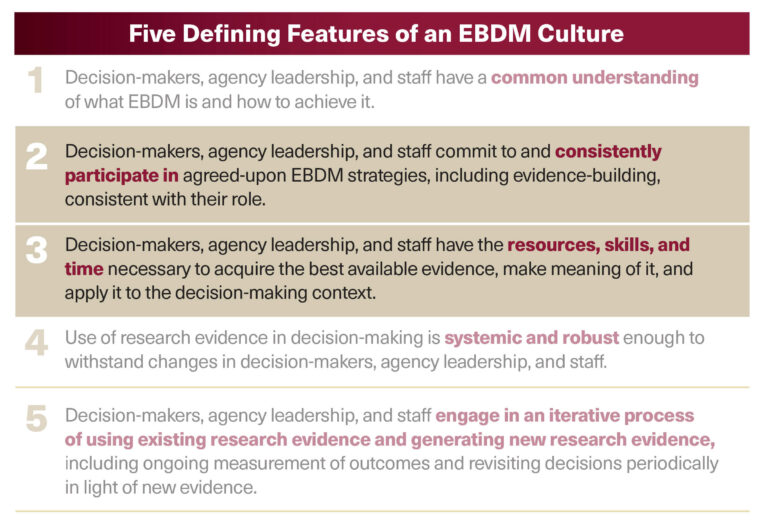

With a clear, shared understanding of what Evidence-Based Decision-Making (EBDM) is (see previous blog post), the next step in creating an EBDM culture is for decision-makers, agency leadership, and staff to commit to routinely using the EBDM approach, consistent with each of their roles.

What is Evidence-Based Decision-Making?

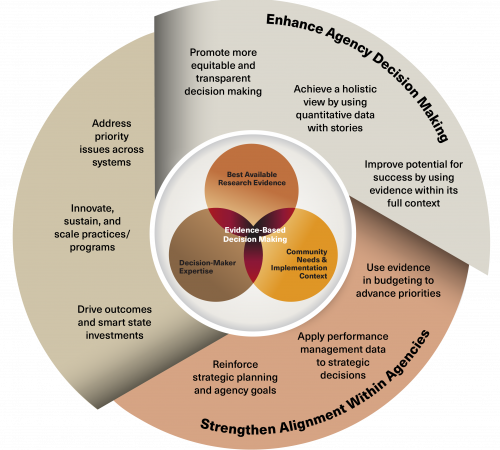

EBDM is the intersection of the best available research evidence, decision-makers’ expertise, and community needs and implementation context. EBDM recognizes that research evidence is not the only contributing factor to policy and budget decisions. Other equally important contextual factors include resourcing, cultural values, community voice, and feasibility of implementation.

The Value of Evidence-Based Decision-Making

We also are working to ensure that the Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB) and staff supporting the Joint Budget Committee of the General Assembly understand the EBDM approach that CDEC is taking. By including community needs, implementation context, and decision-maker expertise, the value of this approach far exceeds the current expectation of both bodies that departments simply present the best available research evidence.

The initial use of EBDM by CDEC advances Colorado’s 5-year vision to build a broad-based culture of EBDM. “CDEC’s early championship of evidence portfolios illustrates the value of tools that align thinking and help everyone look at recommendations with a shared evidence-based frame in mind,” says Dr. Everson. “We look forward to replicating this support tool with other interested state agencies to continue the momentum.”

In our next blog post, we’ll explore the remaining features of an EBDM culture—ensuring evidence is systemic and robust and engaging in an iterative process of using existing and generating new research evidence.